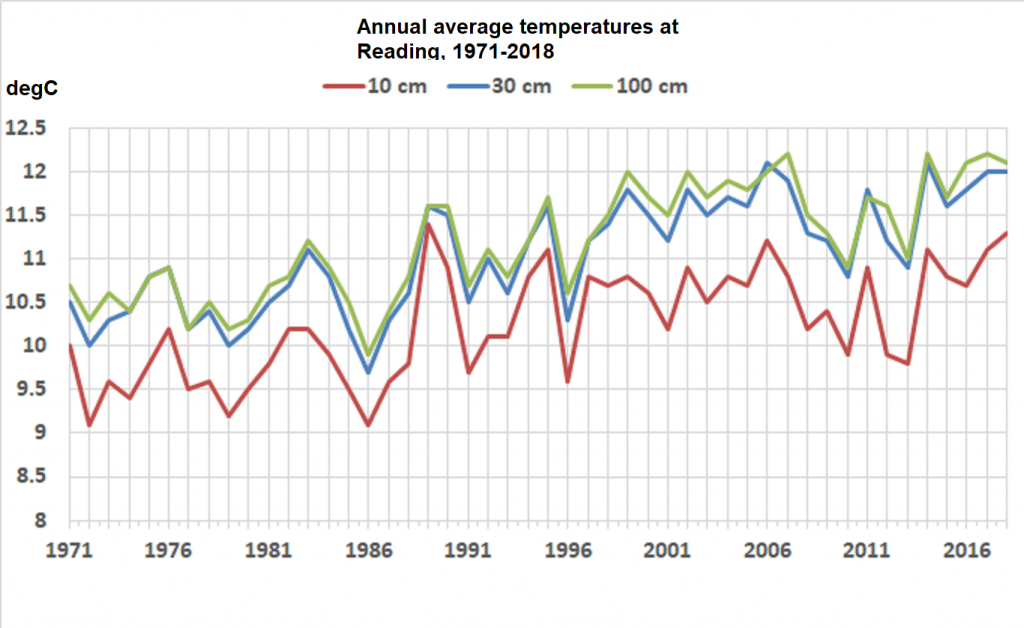

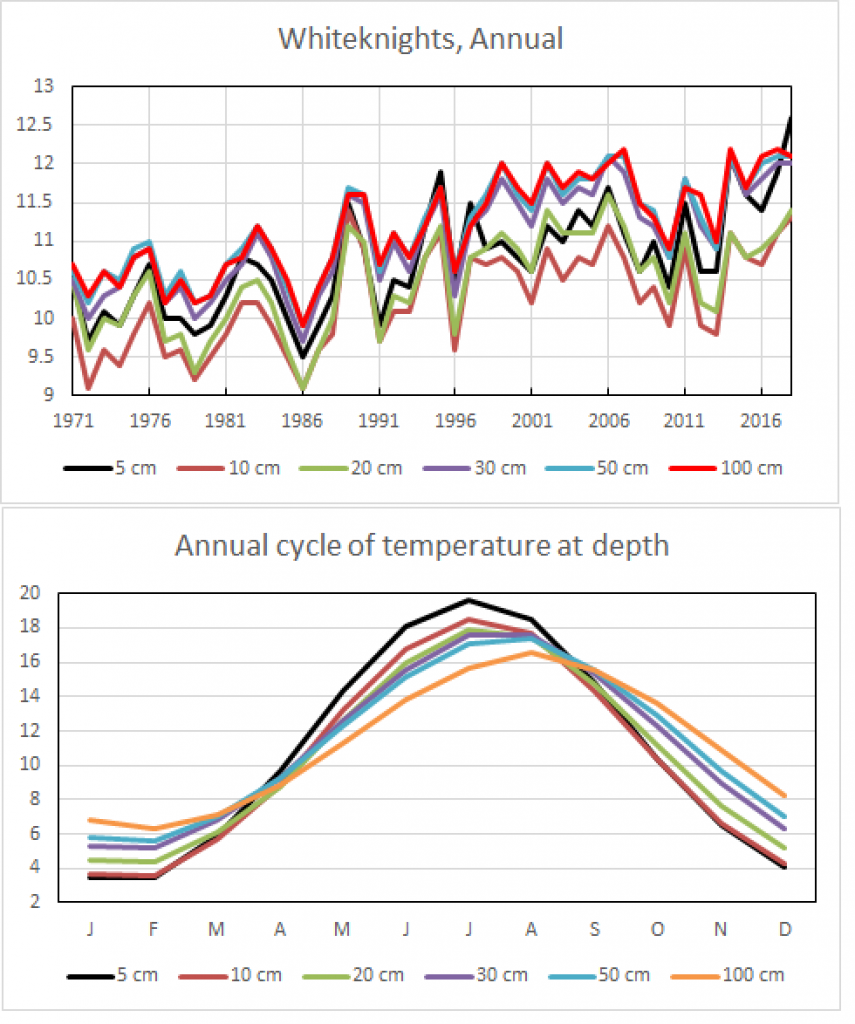

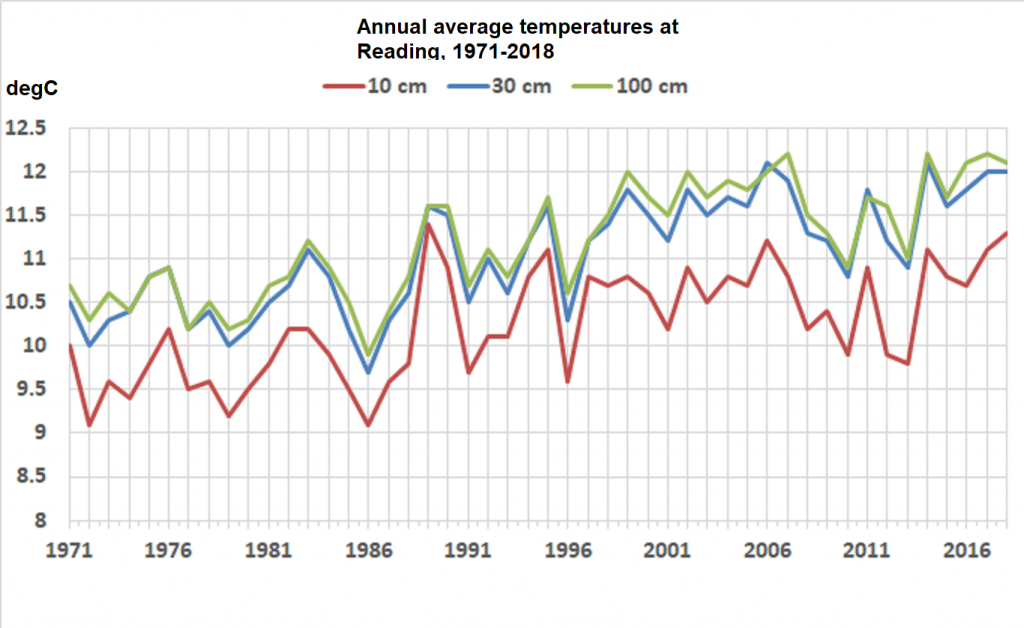

It is not just air and ocean temperatures that are warming through climate change – the soils are warming too. At the University of Reading we have monitored underground temperatures every day since 1971 from 10cm to 100cm depth. There is a clear warming observed at each depth

The time series for 30cm depth can be extended back further to 1941 using observations from nearby sites – Maidenhead, Hurley and an older University campus (London Road*). The variations between overlapping site records are very consistent and more than 1.5°C warming has been observed overall in the last 80 years.

(Added 12th October 2019)

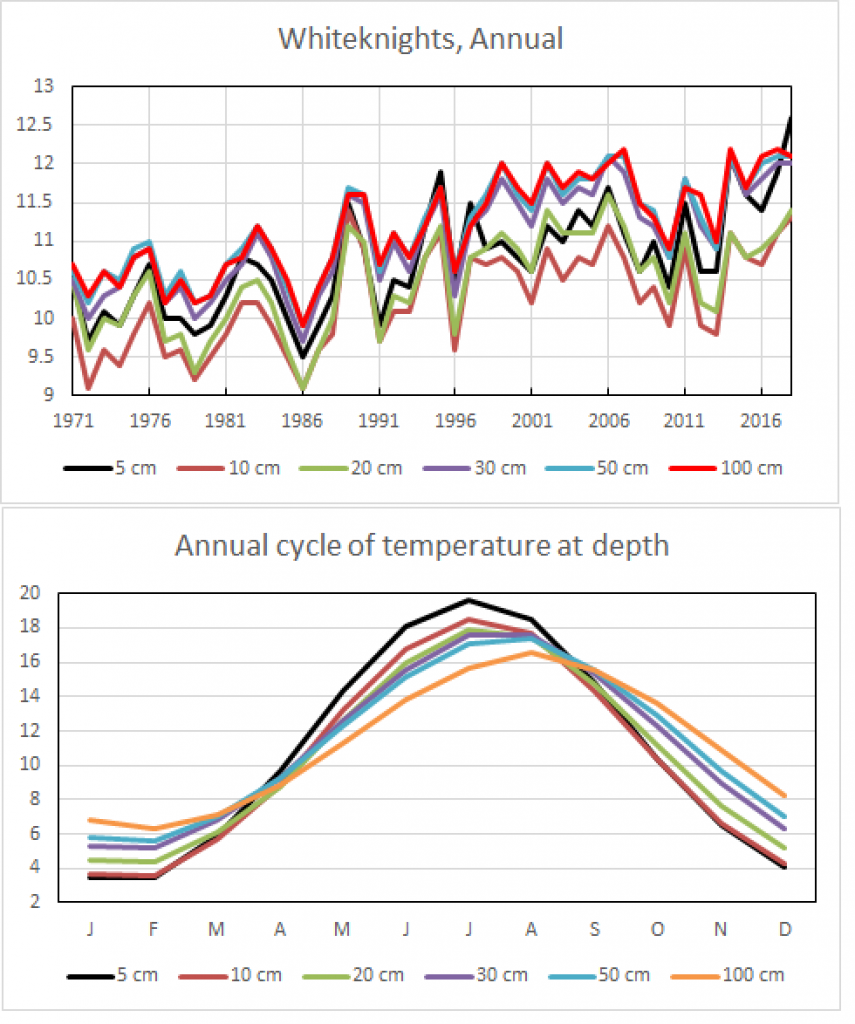

Data for other depths exists also. The seasonal cycle shows how different depths respond to the seasons, with deeper depths being lagged compared to the surface and smaller variations over the year. 10cm depth is coolest in the annual average, with 50-100cm being the warmest.

Graphics and analysis by Roger Brugge, University of Reading.

* Note the London Road campus is about 0.5°C warmer than the other sites, and this difference has been corrected for in the black line.